“As far back as I could remember, I always wanted to be… Elvis.”

The King had died the previous summer, and we were all still in mourning. Try as we might to ape the ‘Memphis Flash’ style, our wardrobe consisted of little more than the customised flares we’d persuaded our mums to taper in until they were suitably pegged. Being mere school kids, the Teddy Edwardian style was beyond us, as none of us could afford drape coats and creepers, so we hit the jumble sales and charity shops looking for box jackets or any attire that was remotely 50s Elvis. I suspect this was the case for a lot of kids of our generation, and this could possibly have been where the Rockabilly style came from—“sartorial elegance on a budget”, as a certain eminent man of letters, Noel ‘Razor’ Smith, would later describe it.

The first Rockabillies I ever saw were in the White Bear pub in Kennington, South London, in the summer of 1978. On Friday nights, the Bear became a Ted joint and was the only place we knew where we could listen to rock-and-roll and get served an underage pint—which we’d manage to make last all night.

The house band were basically squares, who put on drape coats for the occasion and did reasonable renditions of standards such as Runaround Sue and Teenager in Love. Occasionally, members of the audience would get up and sing something. Gary Glitter’s son did ‘Won’t You Wear My Ring’. On another occasion, some Irish guy did Wooden Heart. It started off brilliantly until he got to the “Muss I’ denn zum Städtele hinaus” part, when it became painfully clear that he’d forgotten about that bit and ended up sounding like he was choking on marshmallows… in a German accent.

One evening a couple of chaps turned up in dungarees, Wellington boots and US military-style buzz cuts! From the mockery their appearance generated, I deduced that previously they’d been Teds but had suddenly converted to a very new and strange religion. All their Ted mates called them silly billies and basically ripped the proverbial out of them, but by the following week, it seemed, everybody had made a beeline for Greek Andy’s barber shop in Brixton and got a ‘buzz cut’ or a ‘Mac Curtis’. Soon everyone under the age of twenty was wearing a lumberjack or donkey jacket and was sporting a Confederate flag somewhere on their person. Rightly suspecting us of being a gang, cops used to stop us and ask why we were all dressed the same. We used to tell ‘em it was a coincidence.

Unbeknownst to us, new rock-and-roll clubs had started to spring up all over London, possibly as a response to Punk, which we’d rejected for being ‘with it’ and trendy. As far as we were concerned, anything ‘in’ was out. Pretty soon, we abandoned the White Bear for a club that would become a catalyst for one of the last genuine British subcultures.

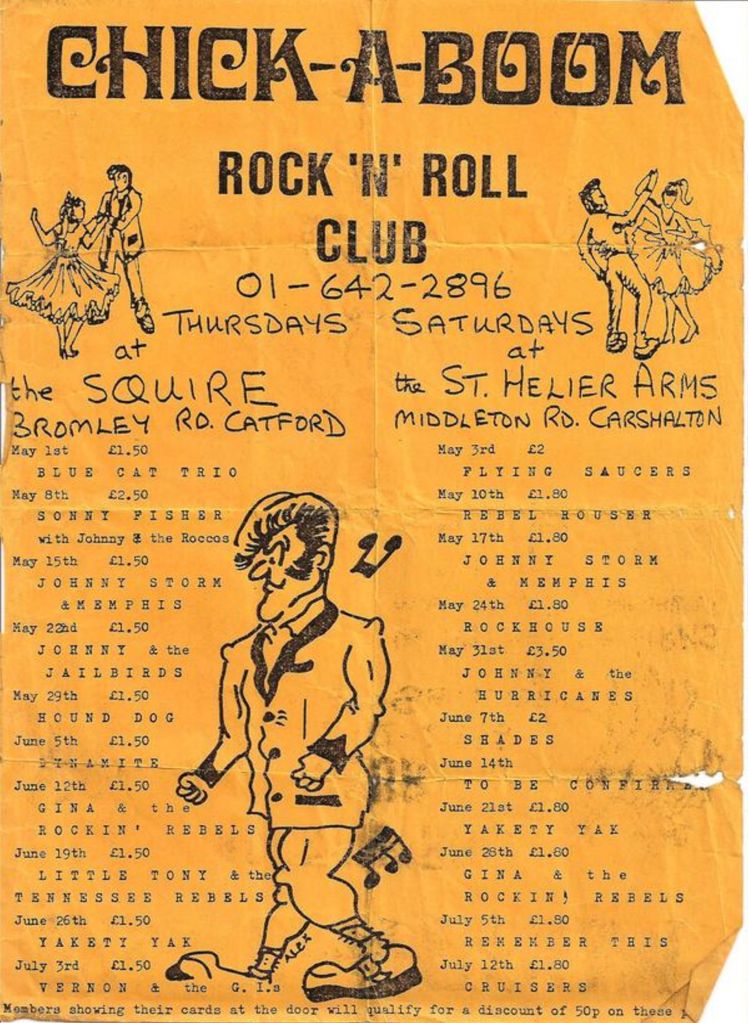

That club was the Chick-A-Boom.

The first time I went to the Chick-A-Boom was to see The Jets. The Jets were a trio of brothers from Northampton who had just appeared on an after-school TV show called ‘Get it Together’.

The show was hosted by a tank-top-wearing children’s presenter named Roy North, who would sing duets with Basil Brush. The Jets had a single out and performed both sides – ‘James Dean’ and ‘Rockabilly Baby’. There wasn’t much in the way of contemporary rock-and-roll that I was aware of, and up until then, the Peggy Sue-esque ‘Deborah’ by Dave Edmunds was about as good as it got. Living in Tulse Hill at the time, I made for the nearest record shop, which happened to be down in West Norwood. I bought the Jets 7-inch single and saw an in-store poster announcing that they were to appear at the Chick-a-Boom Rock-and-Roll Club at the St. Helier’s Arms in Carshalton. I’d never heard of it, but come Saturday night, I was there.

This huge pub had been built on the St. Helier estate in a leafy suburban outpost in the mid nineteen thirties and had sustained a reputation for violence throughout its history until it was demolished sixty years later. Bestowed with the dubious accolade of being ‘the most dangerous pub in London’, I was, as a wide-eyed kid, oblivious to the venue’s fearsome reputation. It didn’t seem that bad to me. For a start, it was only the second pub I’d ever been in, so I assumed that punch-ups were an essential feature of public drinking houses. Also, I was living on the High Trees estate in Tulse Hill, where random acts of brutality were an everyday occurrence. The main problem for me was the two buses it took to get there and the complete lack thereof to get back when the place closed. The first time I got stranded, I called the cops from a phone box. I thought they’d be only too keen to give a lift to a half-drunk fourteen-year-old staggering around alone in the early hours of a Sunday morning. Wrong!

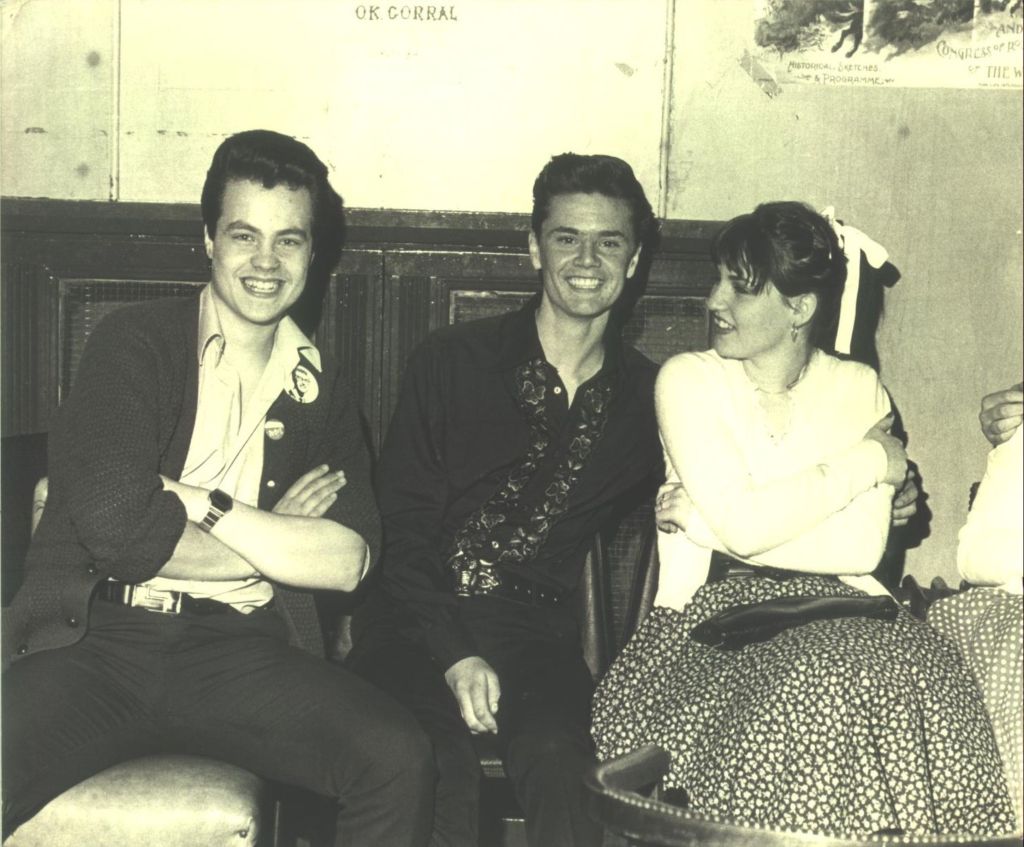

Approaching the St Helier’s Arms for the first time was like walking into a time warp. The forecourt was a tableau of tattooed hipsters barely older than me sitting on the bonnets of their primaeval cars—immense glossy slabs of chrome and polished lacquer. Immaculate pompadours and kiss curls crowned surly, sullen faces—their girls wedged between tight-jeaned knees, lips of stop-sign red, heaving with cleavage and loaded with whispered sweet-everythings…

The club (I believe) was run by a guy called Barney and his brother Jerry, who ran several rockin’ events around the South London area. Jerry was the DJ, and Barney doubled as doorman, bouncer, chief cook and bottle washer. The front bar was always packed with Squares and Smoothies who, until chucking-out time, pretty much stayed there. It was in the rear function room where the Chick-A-Boom operated, and it was here I paid my £1.40 (£1.00 for members), passed a small record stall and entered the main room. ‘Race With the Devil’ pummelled the speakers and rebounded around the place like King Kong had thrown a Buick through the window. The floor was packed. Circle skirts rose, revealing pale bum cheeks and stocking tops. Stiletto heels stepped and kicked. The place was a bop and a strolling mass of velvet, chiffon and sharkskin. Rock ‘n’ Roll heaven was real, and it was in f**kin’ Surrey!

The Jets took the stage—a small, curtained semi-circle, flanked with Grecian-style columns—and to this day I can still remember the tune they opened with: Johnny Burnette’s version of `Please Don’t Leave Me’. On the ‘Get It Together’ TV show, the singer, Bob, had played a big semi-acoustic guitar and looked like Eddie Cochran, but here he played a battered slap bass held together with tape. I’d never seen a proper live band before and was blown away by the power of it all. I spoke to them after the gig, and their guitarist, Ray, handed me his Fender Telecaster. I’d never held a real Fender either. It was cream-coloured, like a big Murray Mint, with chrome buttons and switches that I barely understood at the time. Gary Busey had used one in The Buddy Holly Story (don’t know why; Holly used a Strat), and I knew this model also loomed large in Johnny Burnette’s legend—used, as it was, by his guitarist Paul Burlison. It was like being handed Excalibur!

For the next couple of years, Saturday nights at the Chick-A-Boom Rock and Roll Club would be both a direction and an addiction.

Among the many other acts that appeared at the Chick-A-Boom were Vernon & the GIs, Rockhouse, The Cruisers, CSA, Johnny and the Jailbirds and Crazy Cavan & the Rhythm Rockers. I remember being particularly struck by the fact that most of the bands I saw used a WEM tape echo machine to get that authentic slap-back echo sound for the lead guitar. So that’s how they did it! Matchbox were big on the scene before ‘I’m a Rockabilly Rebel’ made them one-hit wonders, but I didn’t really go for them. For a start, they seemed ancient to me then, and their amps looked seriously modern and hi-tech. Years later, of course, I discovered that some of their members had been in Gene Vincent’s backing band when he was in England and now realise why they were held in such high regard.

There were also authentic 50s artists such as Marvin Rainwater, Sonny Fisher, Sleepy LaBeef, and Ray Campi. What the bands wore was scrutinised very carefully for evidence of non-authenticity. The presence of quiffs was de rigueur, and drain-piped or pegged trousers were next on the list of essentials. Any deviation would bring charges of being a `plastic’. It can’t be stressed enough that to be considered a `plastic’ was the ultimate shame. The horrors of a recent appearance from Buddy ‘Party Doll’ Knox, with his perm, became the material you would one day scare your kids with. “If you don’t go to bed, Buddy Knox’s perm will sandpaper your eyelids off.”

Although there were a few hairstyles bordering on the mullet among Campi’s Rockabilly Rebels, he got the ‘all clear’, and they f***ing rocked it! A few years later, I was in Hollywood, staying with ‘Rollin’ Rock’ legend Jimmie (Lee) Maslon, who claimed to have been the lead guitarist in Campi’s band at the time that I saw him—although I didn’t remember for sure. Jimmie gave us Campi’s number. My brother Vince left the worst rockabilly joke in the history of laughter (don’t ask) on his answer machine. Campi called back and said, “That girl’s got problems.”

As for punch-ups, there were at least a few every time I went to St Helier’s, and it wasn’t just with the Smoothies and Squares in the front either. Strangely, there was a lot of resentment from the older Teds towards the Rockabillies, which often culminated in mutual slappage. It was always the same procedure; you’d be standing there talking to someone, and behind you, you’d hear a table scrape, a glass smash and then… maximum violence immediately! Within seconds, the ‘cats and the kittens of old Bop Street’ would be swinging from the light fittings like a scene from The Oklahoma Kid. Although I got caught up in a few skirmishes, I was generally up front and centre-stage, checking out what guitars the bands had and how they did those Cliff Gallup solos while everyone else was out in the carpark throwing each other up in the air. There was a kitchen appliance place next door (if my memory serves me correctly, and it often does), and their window went through every other week. I don’t think I ever had a fight in the place that was intentional. It would all kick off; you’d catch a dig meant for someone else, then it was clobberin’ time, and you had no idea how or why. Still, ’twas all in good fun.

One time, it was the aforementioned sequence, only with the addition of a girl screaming, “No, Razor, no!” I looked around to see a mate of mine called Noel standing on the seats about to bottle some bloke. The bloke made a fast exit, and this skirmish came to nothing, but this was the first time I’d heard the term `Razor’ being applied to a kid (whom with his brother Mick) I’d more or less grown up with. I hadn’t seen him for a couple of years, as he’d been in and out of remand centres and was then out on temporary release from Rochester. The next time I would hear anything from him would be a quarter of a century later when he was serving life for armed robbery and had just wowed literary circles with his acclaimed crime memoir A Few Kind Words and a Loaded Gun.

By 1980, the game was up. The Stray Cat’s Runaway Boys and the aforementioned I’m a Rockabilly Rebel had turned a thriving scene into a six-month fad. For many, this was their entry point, but for me it was over.

The most exciting thing about the late 70s ‘rockin’ scene’ was that I was discovering Joe Clay, Ronnie Self and Billy Lee Riley in the same months I was first hearing Elvis Costello, The Clash and The Jam. I would soon realise that in terms of power and attitude, British Rockabilly was as much an embrace of Punk as it was a rejection. They were exhilarating days. Incredible contemporary music was being made, but more was being resurrected from the shadowy crypts of obscurity, and for me… it was the Chick-A Boom Rock and Roll Club that rolled away the stone.

This piece was originally written for Milkcow Vintage Magazine around 2011, which folded before it was published. Excerpts feature quite heavily in Paul Wragg’s very excellent hardback, ‘Teds, Rebels, Hepcats & Psychos – The Story of British Rockabilly’

It now appears in its entirety in Save the Bomb!: The unhinged, scattershot intel of A. D. Stranik available from Amazon: https://amzn.eu/d/9gO7686

Leave a comment